US citizens can gamble on the upcoming election on Robinhood, the financial nihilism app announced. Robinhood has termed this “unlocking a new asset class that democratizes access to events as they unfold.”

Let’s pause — I would like to reflect on this incredible phrase, about an asset class that democratizes access to events as they unfold. See, I thought we all had access to the events of the election because we all exist in reality and can find out about them. But apparently, if we can’t gamble on an event, it isn’t happening. This is a fascinating vision of metaphysics, and I would like to hear more about it. No one bet on my birth, for instance, and thus there is no asset class relating to my existence. So am I real?

I’m kidding. Obviously whoever wrote that is just not very good at sentences. No, I want to get down to the heart of the matter here, which is signaled by the phrase “democratizes access.” This phrase sits right next to “financial inclusion” in the lexicon of people who are trying to take your money. “Democratizes access” is one way you can describe “opening a betting market,” but I don’t think it’s the most accurate one!

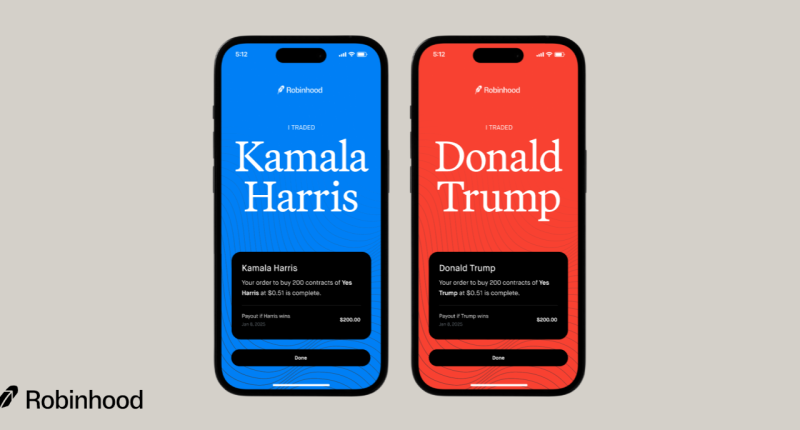

Here’s what Robinhood will let users do, starting today. If you believe Kamala Harris or Donald Trump will win the presidential election, you can purchase an “event contract.” You can trade these contracts for real money; they are a kind of derivatives contract. Robinhood’s exciting new investment opportunity comes after the Commodities Future Trading Commission lost a lawsuit against a platform, Kalshi, that offers political event contracts. That case is being appealed, but won’t be decided before the current election.

Look, I’m aware there are lots of election markets available, because a group of people have decided that the framework of gambling is useful everywhere else. Their given reasoning is that it helps with figuring out events’ probability. (I strongly suspect the actual reason is just that it expands the field of shit to bet on.) Some even go so far as to write whole books justifying their gambling habit as a superior understanding of statistics; others wind up in jail for gambling with other people’s money, continuing to bet on the winning an appeal.

Anyway what’s really fun about election markets is that they can skew easily. For instance, Polymarket has admitted that a single French bettor is responsible for enormous bets that Donald Trump will win the presidential race. So while the polls show the candidates in a close race, Polymarket placed Trump’s odds of winning at 62 percent. Are betting markets accurate? Well, no, not always.